Brand portfolio strategy and architecture are critical components of a successful brand strategy. These are complex, highly nuanced topics, with entire books written about them. Unlike many other elements of brand strategy, most of the fundamental theories and premises of this topic are as relevant today as they were when they were initially developed.

At its core, brand portfolio strategy dictates the number of brands that a company’s portfolio should contain and how to deploy those brands within the business and in the market. It also provides a long-term approach to grow the business by establishing strategic roles for each brand, including what each should contribute to the company. Finally, brand portfolio strategy also dictates the relationships (if any) brands within a portfolio should have with one another. That final component, relationships between brands, is often referred to as brand architecture. While the terms “brand portfolio strategy” and “brand architecture” are often used interchangeably, we will refer to the latter as an important (but distinct) component of the former.

One of the reasons brand portfolio strategy has become so popular in recent years has been the elevated stature of brands in general. If brands truly represent a company’s most intangible assets, it stands to reason that establishing the optimal mix is a high priority. The same is true of managing the brands to ensure maximum marketplace relevance and internal efficiencies.

The increasing prominence of merger and acquisition (M&A) activity has also played an important role. A robust portfolio and brand architecture strategy can significantly improve the odds of M&A success and strategic growth. The better defined the strategy, the more likely a company will be able to keep brand top of mind, value an acquisition properly, and leverage the new brand assets.

As large, multinational companies have acquired more businesses, many have not taken the necessary steps to prune and optimize their brand portfolios post-M&A. The results have been bloated brand portfolios that confuse customers and other external stakeholders, limit internal efficiency, and increase costs. Perhaps the most high-profile example of remedying this situation occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s when Unilever slashed its global portfolio from 1,600 brands to around 400, boosting financial performance across the board in the process.

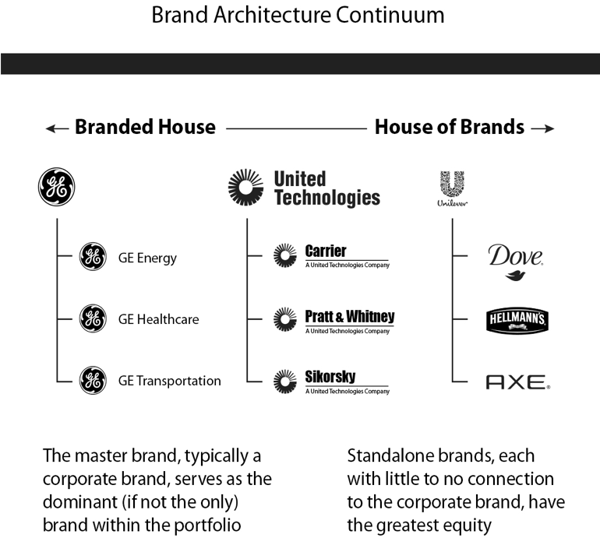

Two books by David Aaker—Brand Leadership and Brand Portfolio Strategy—were instrumental in helping companies distinguish between different types of brands (e.g., sub-brands, co-brands, endorsed

brands, descriptive brands) and their roles in driving competitive advantage and profitable growth. Perhaps most notably, Aaker’s work produced a continuum framework for brand portfolios that is still widely embraced today.

In Brand Leadership, Aaker refers to one end of the brand portfolio spectrum as a “branded house.” This is a portfolio in which the master brand (typically a corporate brand) acts as the dominant brand within the portfolio. Here, descriptive sub-brands have little to no role in establishing market-facing equity or driving business results. In the B2B sector, logistics provider FedEx is an excellent example of this approach. It identifies the different business units as variations of the corporate brand (e.g., FedEx Ground, FedEx Express, FedEx Freight, and FedEx Office).

At the other end of the spectrum is what Aaker named a “house of brands.” In this scenario, independent, standalone brands—each with little to no connection to the corporate brand—have the highest equity and represent the primary face to the market. Newell is an excellent example of the house of brands strategy. Newell is the little-known primary brand, under which come the well-known subordinate brands including Rubbermaid, Sharpie, Elmer’s, Coleman, and Calphalon.

Managing brands in an organized way helps avoid customer confusion and promotes product-development and marketing efficiencies. Furthermore, killing off weaker or ill-fitting products frees marketers to focus resources on the stronger remaining brands and to position them distinctively. It thus reduces the complexity of marketing efforts and increases the efficiency and effectiveness of media and distribution channels.

Recent Posts

Posts by Topics

- Brand Strategy (57)

- Brand Strategy Consulting (28)

- Brand Differentiation (27)

- Customer Experience (24)

- Brand Positioning (22)

- Marketing Strategy (9)

- Brand Extension Strategy (8)

- Customer Behavior (8)

- Brand Architecture Strategy (7)

- Brand Extension (7)

- Brand Growth (7)

- Brand Portfolio & Architecture (7)

- Brand Purpose (7)

- Brand Value Proposition (7)

- Brand Engagement (6)

- Brand Portfolio Strategy (6)

- Brand Storytelling (6)

- Rebranding Strategy (6)

- Brand Awareness (5)

- Brand Image (5)

- Branding (5)

- Rebranding (5)

- Technology (5)

- B2B Brand Strategy (4)

- Brand Experience (4)

- Value Proposition (4)

- Brand Extendibility (3)

- Brand Metrics (3)

- Brand Repositioning (3)

- Corporate Branding (3)

- Differentiation Strategy (3)

- Measurement & Metrics (3)

- Brand Engagement Strategy (2)

- Brand Portfolio (2)

- Brand Promise (2)

- Brand Voice (2)

- Digital Marketing (2)

- Digital and Brand Experience (2)

- Employee Brand Engagement (2)

- Brand Architecture (1)

- Brand Development (1)

- Brand Equity (1)

- Brand Identity (1)

- Brand Measurement (1)

- Brand Name (1)

- Brand Strategy Consultants (1)

- Brand Strategy Firms (1)

- Digital Strategy (1)

- Internal Branding (1)

- Messaging (1)