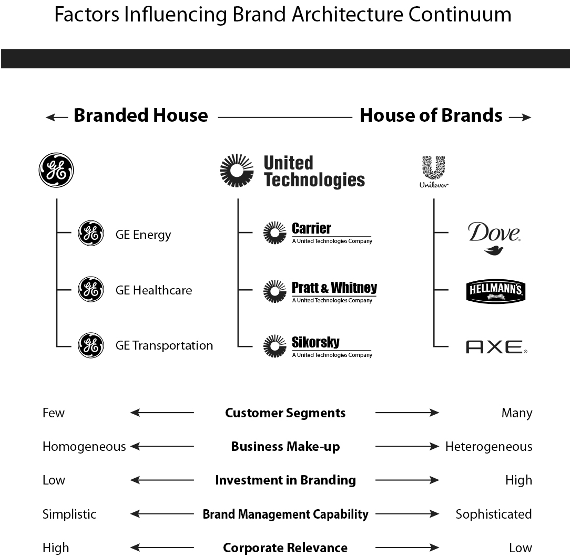

At its core, brand architecture defines the direct relationships among brands in a business. It describes how a company organizes, manages, and markets its brands. There are many different approaches to brand architecture, impacting how customers perceive your business, how you launch a new product or service, and how to integrate other brands into the existing portfolio.

Whose House Is It? Branded House vs. House of Brands

Choosing the right brand architecture to complement your products or

services and your business goals is a critical component to building a sound reputation. In 2000, David Aaker did a great job of proposing a brand relationship spectrum to explain how offers in a portfolio relate to their corporate parent brand. The spectrum, along with those specific terms, is still used today by marketers who strive to identify the right approach to structuring their brand portfolios.

While factors vary by circumstances, several seem to apply to every company, regardless of size, industry, or other factors when choosing a brand architecture approach. Following are five considerations for companies deciding where to reside on that spectrum.

While factors vary by circumstances, several seem to apply to every company, regardless of size, industry, or other factors when choosing a brand architecture approach. Following are five considerations for companies deciding where to reside on that spectrum.

While factors vary by circumstances, several seem to be applicable to every company, regardless of size, industry, or other factors when choosing a brand architecture approach. Following are five considerations for companies deciding where to reside on that spectrum.

1) Number of Customer Segments

Companies should consider the number of distinct customer segments they serve and the number of segments they are attempting to target. For the most part, a well-positioned brand targets a single customer segment. That brand can serve only that segment—plus, at most, one or two others—exceedingly well.

It stands to reason that the more distinct customer segments in a market (and the greater number of those segments a company seeks to serve), the more brands required to do so effectively. In this scenario, companies tend to lean toward the house of brands side of the spectrum.

2) Range or Breadth of Offer

The range or breadth of offer is closely related to customer segments. One of the fundamental premises is how brands can (and should) be defined by something more than the product category or categories in which they compete. However, brands also have limitations in how far they can stretch across different categories.

Regardless of the strength of equity, there are some categories in which most brands simply won’t make sense. Therefore, all other things equal, the greater the number of product categories in which a company competes, the more likely its portfolio will need to reside on the house of brands side of the spectrum.

However, we can find exceptions in this category in B2B organizations. General Electric is often cited as the quintessential branded house because its corporate master brand has demonstrated relevance across diverse industries and product categories ranging from transportation and energy to healthcare and industrial.

3) Corporate Brand Relevance

Corporate brands can have varying levels of market relevance based on several factors — one, is the nature of the business. In some businesses, the company behind the products and services is more important than it is in others.

Professional services is an industry in which the master brand is vital. Clients often buy the brand as much as the individual service offerings provided by the firm. In these cases, going to market with the corporate brand in a driving role is logical. Following this pattern of thought, firms such as McKinsey & Company, Boston Consulting Group, KPMG, and Ernst & Young are quintessential branded houses that trade heavily on the equity they’ve built in their master brands.

Another factor is the extent to which a company chooses to invest in developing its corporate brand. Examples include SC Johnson, ExxonMobil, Procter & Gamble, and The Coca-Cola Company. Once again, all other things equal, the more established and relevant the corporate brand is, the greater its ability to reside on the branded house end of the spectrum (whether it chooses to do so or not).

4) Investment in Branding

How much a company is prepared to invest in brand-building — and not just its corporate brand — in part determines where on the brand portfolio spectrum it should reside. Brands are valuable assets and require significant investment to develop, launch, and maintain. This includes expenses and ongoing investments, such as advertising, promotion, market research and insights, visual identity and assets, and digital activation. Because of these costs, a house of brands portfolio requires far more financial resources to support than a branded house portfolio.

5) Commitment to Talent Development (in Branding)

In addition to financial resources, brand management takes human resources. Companies need human talent to build and maintain strong brands over time. Therefore, organizations must consider the extent to which they’re willing to invest in developing and recruiting employees with the required skills to drive brand leadership.

Importantly, this applies to both the creative and strategic sides of brand building. While some components can be outsourced to consultants and agencies, a house of brands portfolio typically requires more internal brand and marketing resources than a branded house portfolio.

No matter where on the spectrum of house of brands versus branded house a company falls, differentiation remains essential to its success. If the brand is not individually compelling (or, in the case of a branded house, cannot rely upon a sufficiently compelling corporate brand), it will fail to break out of the increasingly common brand monotony of modern marketing.

As a brand architecture firm, our consultants’ extensive expertise covers all aspects of brand architecture strategy. Contact us to learn how we can help grow your brand.

Recent Posts

Posts by Topics

- Brand Strategy (57)

- Brand Strategy Consulting (28)

- Brand Differentiation (27)

- Customer Experience (24)

- Brand Positioning (22)

- Marketing Strategy (9)

- Brand Extension Strategy (8)

- Customer Behavior (8)

- Brand Architecture Strategy (7)

- Brand Extension (7)

- Brand Growth (7)

- Brand Portfolio & Architecture (7)

- Brand Purpose (7)

- Brand Value Proposition (7)

- Brand Engagement (6)

- Brand Portfolio Strategy (6)

- Brand Storytelling (6)

- Rebranding Strategy (6)

- Brand Awareness (5)

- Brand Image (5)

- Branding (5)

- Rebranding (5)

- Technology (5)

- B2B Brand Strategy (4)

- Brand Experience (4)

- Value Proposition (4)

- Brand Extendibility (3)

- Brand Metrics (3)

- Brand Repositioning (3)

- Corporate Branding (3)

- Differentiation Strategy (3)

- Measurement & Metrics (3)

- Brand Engagement Strategy (2)

- Brand Portfolio (2)

- Brand Promise (2)

- Brand Voice (2)

- Digital Marketing (2)

- Digital and Brand Experience (2)

- Employee Brand Engagement (2)

- Brand Architecture (1)

- Brand Development (1)

- Brand Equity (1)

- Brand Identity (1)

- Brand Measurement (1)

- Brand Name (1)

- Brand Strategy Consultants (1)

- Brand Strategy Firms (1)

- Digital Strategy (1)

- Internal Branding (1)

- Messaging (1)